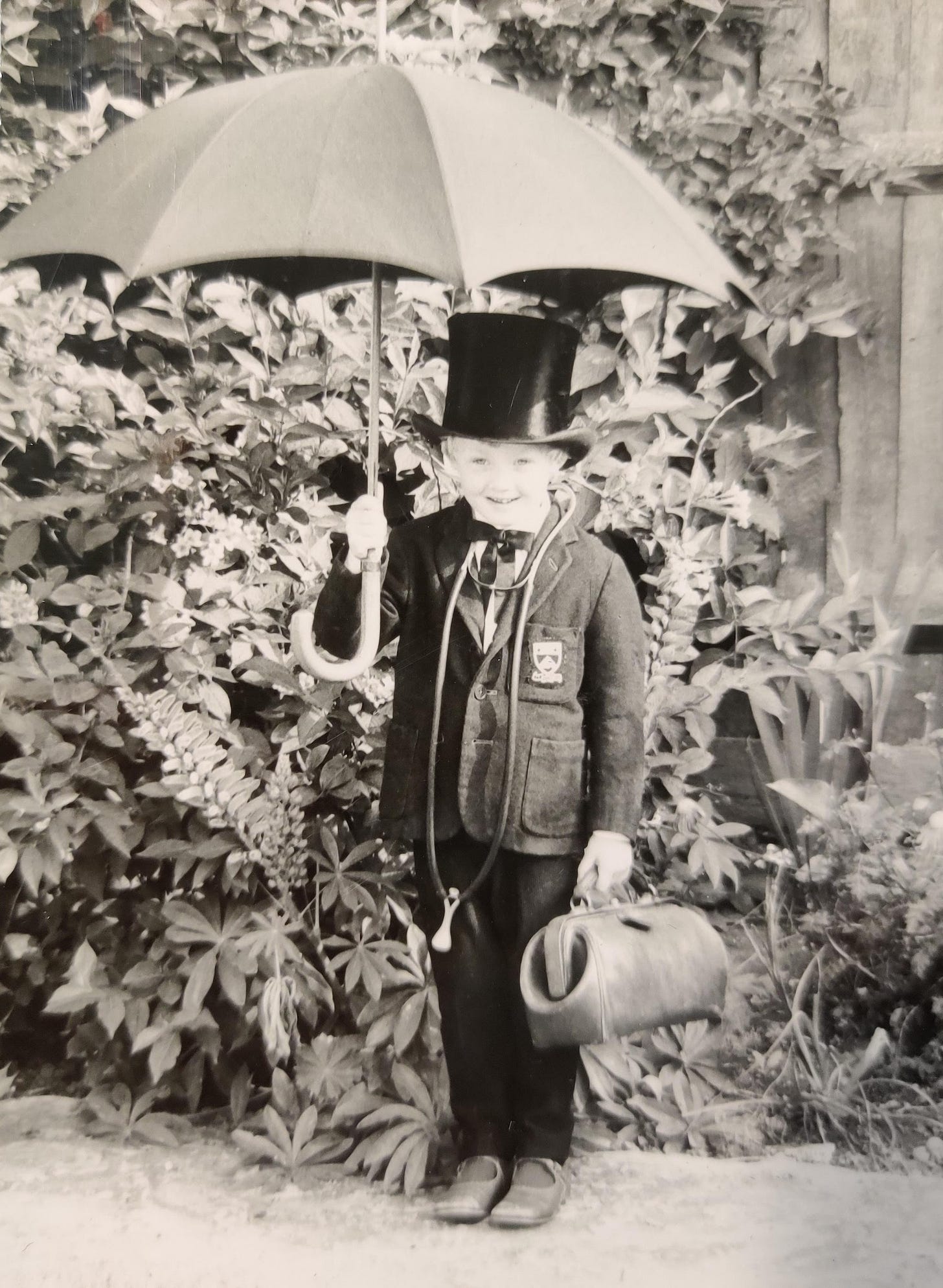

Life With a Doctor Parent: Unexpected Benefits and Challenges

What it was like growing up as a doctor’s daughter in 1970s and 80s England

Mum removed the thermometer from my mouth, and her eyes widened in horror.

107 °F!

Without a word, she fled the room. A minute later, Dad appeared, holding the thermometer. He glanced at me, shook the instrument a few times, and instructed me to put it back under my tongue. Then he stood looking out of my bedroom window, hands clasped behind his back, waiting patiently.

Two minutes later, when he checked, my temperature was down to a more reasonable 102 °F.

“What happened with the thermometer?” Dad asked.

“Nothing. I just washed it with soap and warm water to kill the germs”, I said.

“Hmm — that water must have been quite warm,” he replied, his eyes crinkling.

Younger me didn’t know that mercury thermometers would remain at the level of the last temperature they’d reached. My father taught me to shake the thermometer to make the mercury return to its base level.

If he’d been momentarily worried about me, he didn’t let it show. Throughout my entire childhood, I never saw my dad panic or lose control over anything — not even the day my mum died.

Doctors see a vast range of patients with ailments from trivial to catastrophic. If they don’t appear to take your itchy arm as seriously as you’d like, it’s because they’re looking through the lens of perspective.

That said, always advocate for yourself to get the best medical treatment available. If you’re worried about a health condition, book an appointment, seek answers, keep your medical records, get a second opinion if necessary and follow up.

As my dad always said, “The squeaky wheel is the one that gets fixed.”

Being a doctor’s child has its pros and cons. Yes, doctors can sometimes pull a few strings to get earlier appointments for family members. But the running joke about doctor’s children is that they’re the last to get treated.

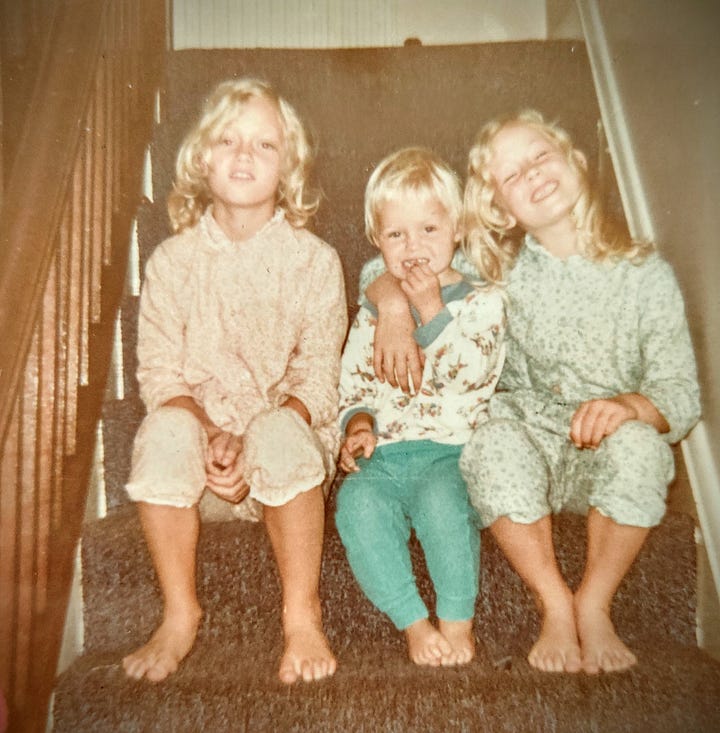

Doctors work long hours. My sisters and I hardly saw our dad during the week. Some mornings, we’d find him shining his shoes in the kitchen before we went to school. The smell of those little tins of KIWI shoe polish brings memories flooding back.

We would meet him at the front door in our pyjamas in the evening if we heard his key in the lock. But most days, we were already in the land of nod before he came home.

Learning first aid

While on holiday, my younger sister Hayley scraped her knee. I was six or seven at the time, and I remember sitting in our old VW van, watching Dad find the first aid kit and open the tin of plasters. I asked if I could put the bandage on my sister’s knee, and he coached me through how to do this properly.

I was proud when Dad told me I’d done an excellent job, and I felt good about helping my little sister. Thirty years later, as a Red Cross first aid instructor, I would smile as the young children in my PeopleSavers classes excitedly shared similar stories of how they’d helped a sibling or friend.

Unconventional ideas on health practices

As a doctor in the 1960s and 70s, Dad had interesting views on nutrition, hydration, and personal care.

He didn’t believe in using sunscreen. Unlike the rest of the family, he didn’t care about getting a “healthy” tan. Instead, he would use the sun as an excuse to sit indoors and watch cricket. On one of the rare occasions we spent the afternoon on Brighton Beach, Dad fell asleep on the pebbles wearing his shorts, socks and shoes.

We placed stones on his large, round belly and ran off laughing to play in the waves. He awoke to a bright red belly covered with big white spots where the pebbles had been. This experience did nothing to convince Dad of the benefits of sunscreen, and I never once saw him use it.

A glass tumbler holding Dad’s red toothbrush stood on the sink in our black and white tiled bathroom. That same toothbrush with the extra stiff, brown bristles remained there for my entire childhood.

Not one to waste money on fancy personal care products, Dad washed his hair with dishwashing soap. We all secretly laughed about this odd practice, but there was no denying Dad had the softest hair!

The fanciest things in our bathroom were a brown Pine Tar soap-on-a-rope hanging from the shower head, Dad’s tube of Brylcreem and a little glass jar with Mum’s colourful bath salts.

Family time

Apart from the summer holidays, Sunday lunchtime was the only time our family of five gathered in the same room. We would enjoy one of Mum’s delicious lunches while discussing family matters, life, the universe, and everything. Dad loved a good heated discussion and would sometimes steer us onto controversial topics to test our mettle.

During lunch, he would usually give a short lecture. At the end of the meal, he would say, “Girls, your task for the afternoon is to — ’’ and set us a mini project, which usually involved looking up information in the encyclopedias in his bookcase. Of course, we never bothered to complete these projects. We’d head upstairs to enjoy a sneaky cigarette in our bedrooms instead.

Smoking

Both of my parents smoked. Mum smoked cigarettes, and Dad pipes and cigars. My sisters and I were probably already addicted to nicotine before we officially started smoking. Even though Dad knew we smoked, he never barged into our rooms to catch us doing it. Once, we heard him come upstairs, and while frantically stubbing our cigarettes, he bellowed, “Good God, what is that awful stench!?”

Dad started smoking at nine years old and continued for the next forty years. It wasn’t until the mid-1960s, when results from the Framingham study concluded smoking was a cardiovascular risk factor, that he started to think about quitting. It took another few years before he finally kicked his 40-year habit.

Food and nutrition

Dad had controversial ideas about healthy eating. He believed that all fat was good for you. We were not allowed to leave bits of fat or gristle on our plates, and we had to sneak them into a napkin if we couldn’t face eating them. If we left food on our plates, our parents reminded us of the starving children in Ethiopia.

At dinner one evening,

“Dad, would you like some salad?”

“Did I have salad for lunch?”

“Yes.”

“Oh well, I’d better not have any more then.”

As for fluids, he thought that as long as he consumed plenty of tea and beer, there was little need to drink water.

Doctor parents can be embarrassing!

When Dad recruited a new locum doctor, they would stay and work in the practice for up to a year. He would invite them to join us for Sunday lunch so they could get to know him better and meet his family.

On one memorable occasion, Dad had invited his new locum, Linda, to lunch. We were fascinated by this slender, angular woman who arrived wearing a beautiful bohemian-style dress adorned with shimmering opals dangling from her ears and neck and an enormous opal ring.

Dad and Linda had been chatting before we all sat down to lunch, and their conversation turned to breast cancer. As we came into the room to sit down at the table, Dad said, “Girls, Linda and I were talking about the importance of women examining their breasts. Do you all examine your breasts regularly?”

My sisters and I, still coming to terms with our newly developing chests, stood speechless in horrified silence before quickly turning and leaving the room.

Keeping up to date

Each morning, torrents of glossy medical magazines and brochures would slide through the mailbox and thump onto the doormat. Dad transferred these to a teetering pile by his green leather armchair. He was expected to keep up with all the new research, treatments, medications, and procedures—a herculean task in pre-Internet days.

Undoubtedly, he became an expert at skimming the pages and picking out the essential information. I would sometimes look at these magazines and be horrified by images of all manner of human medical misery. It made me feel grateful for my lot in life.

Computers

In the late 1970s, Dad and his partners were invited to attend a big medical conference featuring a new-fangled piece of technology—the computer. Dad’s partners decided not to go because they couldn’t imagine the benefits of these mysterious machines. None of them understood the potential applications of computers or could foresee how they would help streamline their systems and medical records.

Dad was excited about the new technology and took the train to London to attend the conference. Highly inspired, he was ahead of his time, having a computer system installed at his surgery to help manage his busy and growing medical practice.

The magical mystery ziplock

When I was 21, I spent three months backpacking and working in the USA on a temporary student visa. Before I left, my dad gave me some first aid supplies, including a small Ziploc bag full of white powder. I asked him what it was, and he said, “Oh, you probably won’t need that.”

I travelled through the USA and worked for a few weeks here and there to fund my trip. During the bus trip to Nashville, I started to feel ill. On arrival, I felt so bad that I checked into a cheap hotel near the station and crashed out in my room, feeling terrible.

Later that day, alone and with a worsening fever, I phoned home for advice. Dad reminded me of the Ziploc with the white powder. He told me to mix it with water and drink it all immediately. I did what he said and went back to bed.

My fever was gone the next day, and I felt much better. The contents of that Ziploc bag are still a mystery. It may have contained a massive dose of antibiotics. Whatever it was, it worked. Good old Dad!

These days, you could never travel with a Ziploc bag of white powder without getting into serious trouble during a security check—but those were different times.

On sieving marmite

After my mother’s death, Dad emigrated to Canada to be near his grandchildren. His apartment was close by, and we’d often pop over to visit him. One day, I noticed something odd in his kitchen. A broken marmite jar was sitting upside down in a sieve over a bowl.

“What’s going on here, Dad?” I asked, amused.

Dad looked at me quizzically as if to say, “Isn’t it obvious?” He explained the jar had broken when he’d dropped it on the floor, and so as not to waste the marmite, he was sieving it into the bowl. Now, anyone who’s eaten marmite knows it’s a thick paste that moves at glacial speed, even when encouraged by tipping the jar upside down.

I would’ve let it go if it hadn’t been for the broken glass in the sieve. However, I felt compelled to point out to my father that if any tiny shards of glass made their way through the sieve and he swallowed them, he might end up in the E.R. Doctor Warden scoffed at my “unnecessary concern.”

Dad rarely threw anything away, always arguing it might come in handy one day. Sieving Marmite was in line with his “Waste not, want not” philosophy, likely influenced by living through WWII.

Being a doctor’s child wasn’t always easy, but I loved my Dad and felt safe knowing he would figure out what to do if we were ever sick or injured. After he died, my sisters and I found some lovely thank you letters and cards from grateful patients. I’m proud of my father and have often wondered how many lives he saved during his working life.

Medicine is a challenging path to choose. I’ve witnessed firsthand some of the difficulties of balancing career and family. Doctors work long hours, make many sacrifices, and endure the heavy responsibility of making life-and-death decisions. They spend their days holding people’s lives in their hands.

If you’re lucky enough to have access to a doctor — and not everyone is — be kind to them.

This story was originally published in The Memoirist on Medium.com